Honor lūdī

(Honor of the Game / The Game of Honor)

This is the third time I’ve accidentally written a book. I began writing a section about the 2025 World Series for my first book (On Moonlight: a film analysis, autobiography, & holistic societal critique) that grew far beyond my initial plans for it; I reached the inescapable conclusion that I was writing a third book when I realized it had grown to 70,000 words with no end in sight. (My second book, Aequilībrium harmoniae: a mathematical analysis of scales, modes, & the circle of fifths, is a lengthy, technically detailed treatise on music theory; Aequilībrium harmoniae is Latin for both The Balance of Harmony and The Harmony of Balance.)

Honor lūdī is paraphrased from one of Dodgers manager Dave Roberts’ favorite sayings, “The game honors you.” It means both honor of the game and the game of honor, owing to the unusual grammar of Latin’s genitive case. I intend both meanings. An exact Latin translation of “the game honors you” would be lūdus te honōrat.

I cover numerous topics in this book, including but hardly limited to:

wasn’t the only player to be successful as both a hitter and a pitcher before .

Along the way, you’ll also learn about such colorful characters as:

With one exception, I mostly don’t follow professional sports. I followed the 1990s Chicago Bulls: , , , , , and were poetry in motion. Until the 2024-2025 Los Angeles Dodgers rolled along, they felt like the only equivalent I’d ever see of the 1920s Yankees’ “Murderer’s Row” in any sport: a candidate for the greatest player of all time and several others who’d be other teams’ star players. I knew I was witnessing something special at the time, and I hardly find it surprising that six members of that team (Jordan, Pippen, Rodman, Kukoč, Parish, and coach ) are now Hall of Famers.

But I think I was mostly a fan of that particular lineup, not basketball itself; after the 1997-98 season, Jordan retired for a second time, and Pippen, Rodman, and Longley were traded to other teams (Parish had already retired after 1996-97, while Kukoč was traded midway through the 1999-2000 season. Parish played 1611 games, which remains an NBA record, though is about a season and a half away from surpassing it). The magic had gone, and I stopped following the sport. (It doesn’t help that, being 5’5”, I never had the slightest hope of developing any aptitude for it myself.)

My first and greatest love among sports is and probably always will be baseball. Reasons for this include:

I briefly wanted to be a baseball pitcher, but I never could learn to throw the ball fast enough, which I’ll put down to lacking the competitive drive truly needed to succeed in team sports. I can occasionally be induced to be competitive in games, but my friends have to stir it out of me.

I must preface all the following remarks by noting that I was born in Atlanta, Georgia. My understanding is that geneticists have isolated this as the key factor in congenital biases against both Game 7 of the 1991 World Series (in which the Minnesota Twins defeated the Atlanta Braves 1–0 in ten innings) and the Toronto Blue Jays (who defeated the Braves in 1992’s World Series). I will admit that objectively, 1991’s Game 7 should qualify as one of the best of all time, but I’m still not over it, and it will never, ever top my “greatest Game 7s of all time” list. (I’ve at least cooled down enough to place it in my top ten, even though I still hate the outcome.)

Moreover, even if I weren’t an Atlanta native, familial loyalty would still obligate me to be a Braves fan: their star pitcher is my second cousin. Sale, a nine-time All-Star, has won a World Series ring, a Gold Glove, a Cy Young Award, and pitching’s Triple Crown. He also reached 2,000 and 2,500 strikeouts with fewer innings pitched than any pitcher in history, unseating first-ballot Hall of Famers and respectively. He shares the MLB record of three immaculate innings (nine pitches, three strikeouts) with first-ballot Hall of Famer and (and current Blue Jays starter) , and he’s the only pitcher ever to throw two in one season (2019-05-08 and 2019-06-05).

In at least one year, he’s led MLB in win count (2024), win-loss ratio (2024), ERA (2024), ERA+ (2024), FIP (2017, 2024), strikeouts per nine innings pitched (K/9IP, 2015, 2017, 2024), home runs per nine innings pitched (2024), FanGraphs pitching wins above replacement (pWAR, 2017, 2024), strikeouts (2017), complete games (2016), and innings pitched (2017). He also led either the NL or AL in Baseball Reference pWAR (2024), complete games (2013), strikeouts (2015, 2024), ERA+ (2014), FIP (2015), K/9IP (2014), and strikeouts per bases on balls (2015). His own Hall of Fame berth is already near-certain, and unless an injury ends his career prematurely, he’ll likely become the 21st and final member of the 3,000-strikeout club, in turn all but ensuring a first-ballot election.

(I’ll have a rundown of several crucial baseball stats after this section.)

For some reason, though, I’ve mostly forgiven the Twins for 1991. I mostly haven’t forgiven the Jays for 1992. I’ve made many painful, even embarrassing revelations about my childhood and adolescence in my ⟨aaronfreed

I’m not even sure it’s the franchise, per se, that I dislike. If anything, I gained a considerable amount of overall respect for the 2025 team for its World Series performance (aside from , whom I doubt I’ll ever forgive his role in the 2017 Houston Astros’ sign-stealing). The team’s relievers made a particularly classy gesture after what was described at the time as a “family emergency” forced Dodgers reliever , whose uniform number is 51, to drop out of the World Series. (This ultimately was revealed to be his infant daughter’s illness; sadly, she passed away on October 26.) I’ll let describe:

“Yeah, I didn’t notice until… after [Chris] Bassitt struck me out, and then I was looking up at the board to see the replay, and that’s when I saw that he had 51 [on his hat], and instead of being mad that I struck out, I was kind of going back to the dugout thinking, ‘Did Bassitt play with Vesia at some point?’ And then, after the game, I saw that everybody had them. For those guys to do that, it’s incredible. They’re trying to win a Series, but they understand that … life is bigger than baseball, and baseball’s just a game. For them to do that, with … where we were at with the stakes? Hats off to them, and I want them to know that … regardless of what happens tonight, we appreciate what they did.”

And the majority of Jays fans have handled a loss that must rival how 1991 felt to us Braves fans with unimaginable grace and class. As usual, a small but vocal minority of fans are ruining everyone else’s reputation.

The reason the Twins escaped my long-time loathing, but the Jays didn’t, is largely due to the behavior of one particularly insufferable Canadian classmate in 1992 who seemed determined to teach everyone a valuable lesson by proving that not all stereotypes are always accurate: for instance, not all Canadians are polite. This was 33 years ago, so I’m not even going to attempt to recount memories of any particular incidents, which I’m sure are horrendously inaccurate. I’ll just say I didn’t know the word Backpfeifengesicht (literally, “a face in need of a slap”: of course the Germans would have a word for this – not just an expression, a single word!) in 1992, but if I had, I’m sure I’d have used it to describe him. To be clear, I don’t condone unprovoked violence, but I was in fifth grade at the time, and few things are more infuriating than a sore winner.

As I said, the majority of Jays fans last year really did nothing to earn my ire. However, I only saw signs personally attacking a specific player from one MLB franchise’s fans this season, and in case you need a hint which franchise that was, here it is: that franchise is not based in the United States. I’d still be more willing to forgive even this had they not targeted one of the nicest, humblest, hardest-working athletes in the sport’s history, a legitimate contender for the greatest to ever play it, and a member of one of this country’s most vulnerable populations besides.

I’m referring, of course, to (Japanese: 大谷 翔平; Hepburn: Ōtani Shōhei), baseball’s nearest equivalent to Michael Jordan in my lifetime, an all-rounder of historically unprecedented caliber. Before I explain why, though, it’s probably a good idea to provide context for the statistics I’ll be referring to throughout this book.

Wins Above Replacement (WAR) is a statistic tracking a player’s effectiveness over that of a replacement player, i.e., a player just brought up from the minor leagues. I won’t bore readers with a description of the exact formulae, especially since there are multiple calculations. The most important ones are:

FanGraphs has its own WAR formula, logically called fWAR. Here’s FanGraphs’ WAR explainer. (Note that FanGraphs doesn’t display pitchers’ total WAR; it’s necessary to add their pitching and non-pitching WAR.)

One of fWAR’s major differences from rWAR is its employment of a slightly modified version of Fielding Independent Pitching (explained below) to calculate pitching WAR; rWAR uses runs allowed per nine innings and attempts to compensate for team defense. This rarely produces as much variance as you might expect. Two Hall of Famers provide major exceptions: fWAR is 49.9% more generous to Jim Kaat (, ), while rWAR is 33.3% more generous to Walter Johnson (, ). I have a very mild perference for rWAR in this category, but it’s so mild that in many cases, I have taken to calculating arithmetic or geometric means of the two statistics; in others, I’ve taken to listing both.

The two calculations also vary significantly in how they handle catcher defensive metrics. FanGraphs takes pitch framing data into account where it exists (2007–present), so I strongly favor it for recent catchers. A particularly noteworthy example comes with St. Louis Cardinals catcher Yadier Molina, the greatest defensive catcher of his generation, who has and , mostly due to defense: Baseball Reference gives him 136 fielding runs against FanGraphs’ 218.4. (Baseball Bits has an excellent video about him.) Likewise, San Francisco Giants catcher Buster Posey has and .

I must emphasize that WAR is not an exact science. had 12.6 rWAR in 1927, while his teammate had 11.9. Was Ruth more effective than Gehrig that year? Trick question: those numbers are too close for us to be sure that he was. On the other hand, Ruth had 14.1 rWAR in 1923; runner-up had 10.9, which is a significant enough margin that we can be reasonably certain that Ruth had a better season. Generally, margins below 1 WAR should be considered within the margin of error, and even a 1-WAR margin is sketchy. A differential of at least 2 WAR is where we can start to be certain that a player has been more effective.

A further wrinkle arises from the fact that WAR is cumulative. That is, an entire season played slightly better than a replacement player can net the same WAR as a few games played far better than a replacement player. I’ve thus created additional metrics attempting to extricate the degree of a player’s efficacy from the duration. This requires some further details, since there are actually three main forms of WAR (though most players not named “Shōhei Ohtani” have had at most two since the National League adopted the designated hitter):

|

Αἱ τρεῖς κεφᾰ́λαιαι κᾰτηγορῐ́αι τοῦ ΠΟΛΈΜΟΥ Hai treîs kephắlaiai kătēgorĭ́ai toû POLÉMOU The three main categories of WAR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name / Acronym | What it’s good for | Who it covers | Who it doesn’t | |

| Defensive WAR | dWAR | Fielding | Pitchers, position players | Designated hitters |

| Offensive WAR | oWAR | Hitting, baserunning | Hitters, baserunners | Players who don’t hit or pinch-run |

| Pitching WAR | pWAR | Pitching | Pitchers, two-way players | Players who don’t pitch |

Having already wandered so far into the trees that I’m afraid of losing sight of the forest, I’ve combined dWAR and oWAR into non-pitching WAR (nWAR, pronounced like noir in film noir), which I’ll sometimes analyze in lieu of oWAR or dWAR. It helps that, while designated hitters don’t have dWAR, pitchers that never hit don’t have oWAR, and position players that never pitch don’t have pWAR, all MLB players have nWAR.

With multiple formulations and multiple categories of WAR, initialisms might get confusing. I’ll consistently use:

| WAR acronyms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Pitching | Non-pitching | Offensive | Defensive |

| Baseball Reference | rpWAR | rnWAR | roWAR | rdWAR |

| FanGraphs | fpWAR | fnWAR | foWAR | fdWAR |

| Seamheads | spWAR | snWAR | soWAR | sdWAR |

| Baseball Prospectus | pWARP | nWARP | oWARP | dWARP |

| Arithmetic mean | apWAR | anWAR | aoWAR | adWAR |

| Geometric mean | gpWAR | gnWAR | goWAR | gdWAR |

WAR is cumulative, but it’s often helpful to evaluate it over specific time spans to compare players’ consistency (especially if their career lengths varied). For this purpose, I’ve created the following metrics:

DWFS, or dWAR per fielder’s season of 600 fielding opportunities (i.e., the fielder’s sum total of putouts, assists, and errors). In truth, this varies widely by position; I simply chose 600 for continuity. On average:

Important note: nWAR ≠ oWAR + dWAR. All three numbers factor in the player’s position; simply adding oWAR and dWAR would double-count the positional adjustment. Thus, nWAR = oWAR + dWAR − positional WAR.

I only focus much on dWFS in a couple of places, largely for two reasons:

I may note it in cases where it’s especially high or especially low, but that’s all.

It’s rare for dWAR to factor into a player’s overall WAR as much as or more than oWAR, but it happens occasionally. Hall of Fame shortstop/second baseman had 30.9 roWAR, 30.8 rdWAR, 17.7 positional rWAR, and 44.0 rnWAR. Hall of Fame shortstop had 32.8 roWAR, 34.3 rdWAR, 13.8 positional WAR, and 53.3 rnWAR. Shortstop had 14.7 roWAR, 39.5 rdWAR, 13.3 positional WAR, and 40.9 rnWAR. Shortstops are by far the likeliest to accumulate huge dWAR values; of the top ten players in rdWAR, all but third baseman and catcher play(ed) mostly shortstop.

As for why I chose Tinker, Evers, and Chance for my first three examples, I refer you to Franklin Pierce Adams’ classic poem “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon”:

“These are the saddest of possible words:

‘Tinker to Evers to Chance.’

Trio of bear cubs, and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Making a Giant hit into a double –

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

‘Tinker to Evers to Chance.’”

One final note is that none of the above metrics should be taken as gospel ratings, especially in cases of small sample sizes. We’ll meet players with high PWMS ratios from relatively few innings pitched, or high OWHS ratings from relatively few plate appearances. These ratings don’t necessarily mean that these players would’ve continued to turn in such excellent results had they done more pitching or hitting. They might’ve (Hall of Famer threw all but one of his innings at age thirty-seven, so he might’ve done even better at a younger age), but in short, the smaller the sample size, the less confidence we should have that a player could’ve maintained a particular play standard across a longer time span.

Win–loss records and win percentage are one of the oldest pitcher efficacy metrics…and one of the worst.

gave up only a hit, a walk, and an unearned run on . He lost. Why? His counterpart, the Dodgers’ , allowed no runs, no hits, and no walks, and the Dodgers made no errors (a perfect game). Was Hendley’s outing bad? No, of course not. The Cubs just couldn’t hit Koufax. That wasn’t their fault: Hall of Famer compared trying to hit Koufax to “eating soup with a fork”.

This is an extreme example, but it goes to show these metrics’ limitations. Decisions (individual wins and losses) are almost useless for relievers, who rarely enter games with blank slates. If I enter a game my team is winning, I’m only credited with a win if I give up at least enough runs to tie the game, then my teammates regain it. Likewise, if I enter one we’re losing, I can only get a loss if my teammates score at least enough to tie the game, then I give up enough runs to set us behind. Effectively, our situation when I enter greatly affects my odds of earning wins or losses, and our manager controls when I enter; I don’t. This is why other stats exist for relievers. Arguably, a high decision count being a red flag for a reliever is the only thing that keeps reliever decisions from being trivia.

Comparing starters’ record and win% to their other stats can provide perhaps surprising insights not on the starters, but on their teammates and opponents. We can conclude that a pitcher with a tied or losing record, low WHIP, and high ERA+ is actually an incredible pitcher who likely suffers from either:

Several similar statistics are meant to track reliever effectiveness. Since 1975, MLB rules have credited a save as occurring when a pitcher:

In a potential save opportunity, a blown save involves giving up the game-tying run (whether or not the runner was already on base). A reliever in the same situation who records at least one out without blowing the save or finishing the game is credited with a hold and is not credited with a save opportunity. Save percentage is calculated by dividing a reliever’s saves by their save opportunities.

These statistics have come in for some criticism; Hall of Fame relievers and each blew over 100 saves but were still extraordinarily effective overall. It’s arguably better to use one’s best relievers strategically in close games than to uniformly use them for every game’s final inning. Sabermetric analysis has clearly demonstrated, however, that the most effective reliever is the previous game’s javelin-throwing starter; no such pitcher has ever lost a World Series game.

Relievers are saddled with broken eggs when:

And they’re credited with mehs if a run charged to another pitcher or an unearned run scores while they’re on the mound. Silver argues that:

“[M]anagers are trying to maximize the number of saves for their closer, as opposed to the number of wins for their team. They’re managing to a stat and playing worse baseball as a result. … [A save] doesn’t give a pitcher any additional reward for pitching multiple innings — even though two clutch innings pitched in relief are roughly twice as valuable as one. And a pitcher doesn’t get a save for pitching in a tie game, even though it’s one of the highest-leverage situations.”

He also argues that goose eggs and broken eggs correlate much more closely (0.78) to the much more complex statistic Win Probability Added than saves and blown saves do (0.50).

Goose Wins Above Replacement is to goose eggs as pitching WAR is to wins. (Unfortunately, Dave Brockie [RIP] is not MLB’s leader in GWAR.) had the best single-season GWAR in 1965, with 79 goose eggs to 7 broken eggs for 7.5 GWAR. His traditional stats looked good enough at 14–7, 1.89 ERA, 24 saves, 119⅓ IP, and 4.2 pWAR, but he was almost unhittable in high-leverage situations. Lifetime save leader also leads in lifetime GWAR with 54.6, but his best season according to GWAR was not 2004 (53 saves, 47 goose eggs, 4 broken eggs, 2.09 ERA, and 232 ERA+ in 78⅔, 4.2 pWAR, 5.4 GWAR) IP, but 1996 (5 saves, 54 goose eggs, 6 broken eggs, 1.94 ERA, 240 ERA+, 107⅓ IP, 5.0 pWAR, 6.6 GWAR).

Yoshinobu Yamamoto got three goose eggs out of three opportunities in World Series Game 7 last year. Will Klein got four out of four in Game 3. In and of itself, that feels like sufficient proof of this statistic’s value.

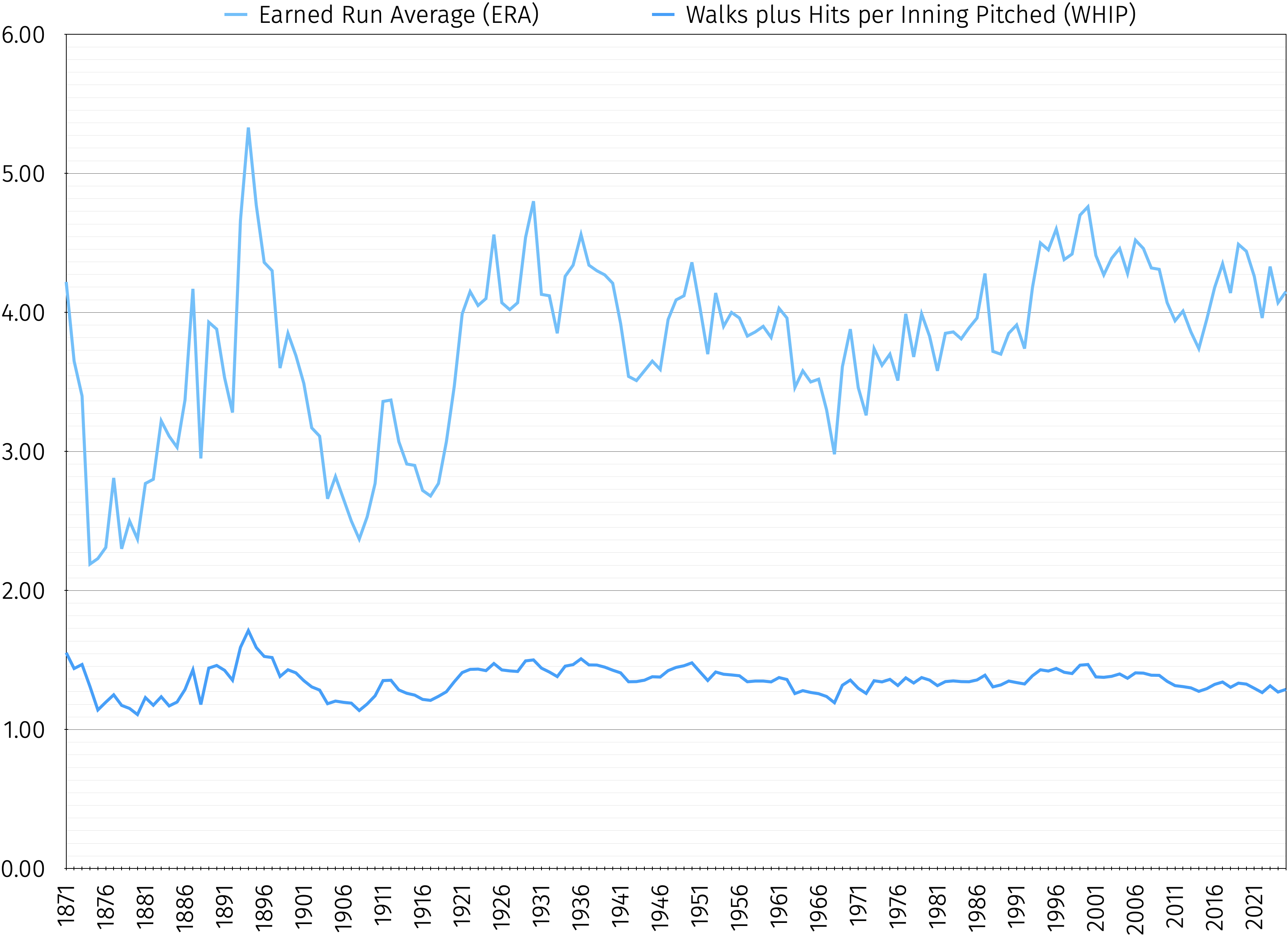

ERA, or Earned Run Average, is a traditional metric of how often a pitcher gives up earned runs, or runs that aren’t the result of fielding errors. A lower number is better. The formula for calculating it is simple: Earned Runs × 9 ÷ Innings Pitched. It has several limitations, but it’s still widely used, partly because it’s easy to understand and calculate. Also, unlike ERA+, it’s possible to calculate for postseason games.

, the all-time career leader, has a 1.816 career ERA. He also pitched exclusively in what’s called the “dead-ball era” because it was extremely hitter-unfriendly. The dead-ball era ended after 1919, coincidentally ’s last season with the Boston Red Sox.

The modern leader, , retired in 2013 with a 2.209 career ERA. Rivera was primarily a reliever, meaning that he worked in smaller spans. Relievers tend to have lower ERAs. , who just retired, has the lowest career ERA among modern starters, with 2.534. The increase in ERA over the years is less due to a decline in pitching quality and more due to rule changes and an increase in hitting quality.

ERA+ has overtaken ERA as one of the most important indicators of a pitcher’s effectiveness in recent years, though it has a few weaknesses (most notably, it isn’t calculated for postseason games, and it’s also more complicated to explain). Unlike ERA, it’s adjusted to factors such as the overall league average ERA and how hitter-friendly the ballpark is – thus, runs allowed at the Colorado Rockies’ Coors Field, which is notoriously hitter-friendly due to being over a mile above sea level, will count less against a pitcher’s ERA+ than runs allowed at the Miami Marlins’ LoanDepot Park, which is, unsurprisingly, at sea level. Perhaps the most important difference from ERA, though, is that a higher ERA+ number is better. This stat’s career leaders are:

The fact that this list spans baseball’s entire history suggests it measures a pitcher’s relative dominance much more reliably than ERA does. Also, although not every great pitcher in history ranks this high on this list (it’s missing , , , , and several other immortals), every pitcher on this list was great. (Even Devlin, who burned briefly but brightly – no one has ever duplicated his feat of throwing literally every pitch his team threw that year, and no one ever will.)

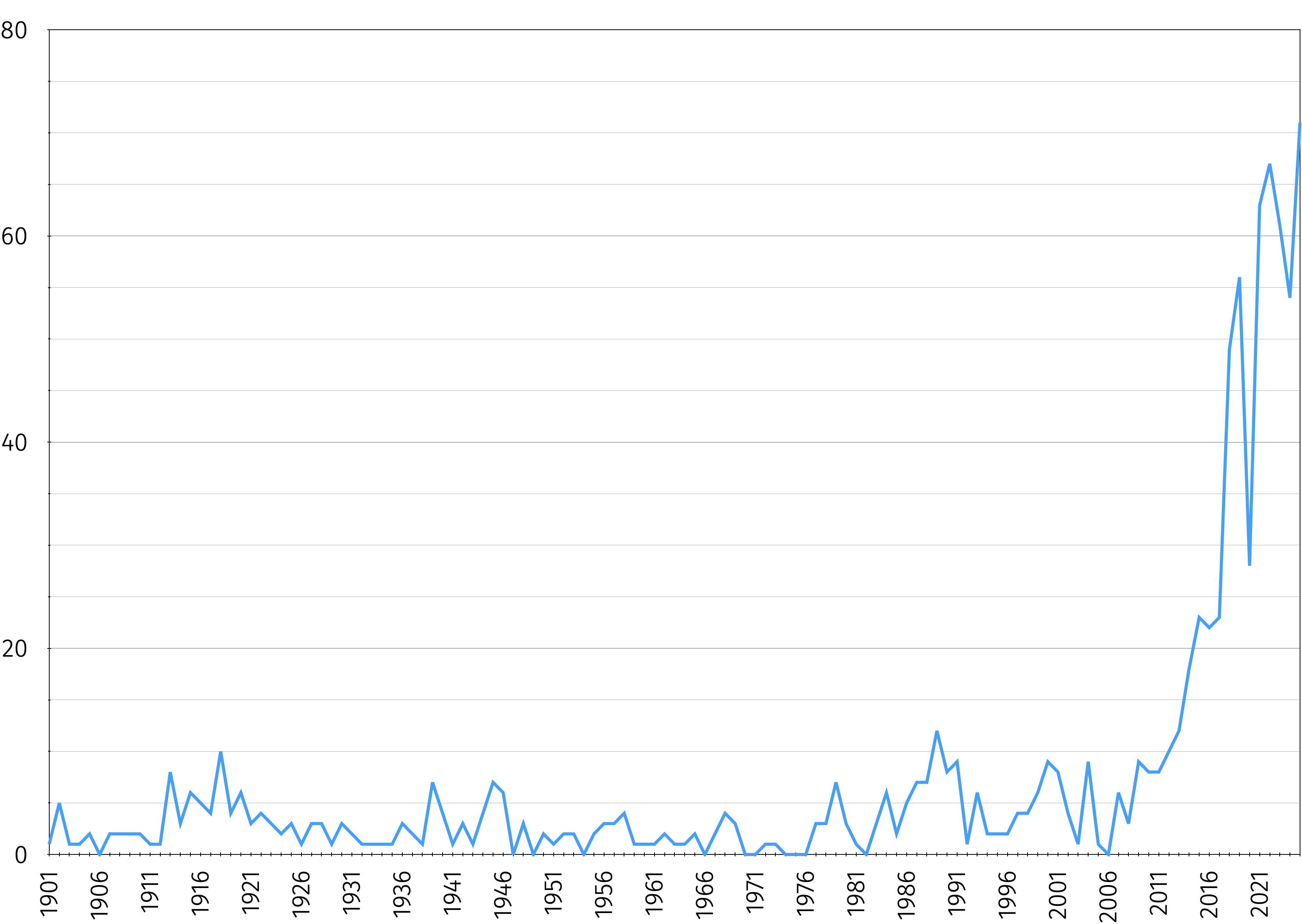

Complete games have become extraordinarily rare. In 1904, 87.6% of games were complete games; in 2024, 0.6% were. This is largely due to increasingly strict adherence to pitch counts, to the extent that it was considered extraordinarily unusual when Yoshinobu Yamamoto threw 96 pitches in Game 6 of last year’s World Series, then another 34 in Game 7. (This is nothing for Yoshi, who’d thrown up to 140 pitches in NPB games, and who throws javelins for practice.) It has been speculated that this may lead to a decrease in reliance on pitch counts, since Yamamoto has been healthy over a career in which he has thrown a lot, while despite the modern obsession with pitch counts, pitchers are suffering more injuries than ever before.

A no-hitter is a game of at least nine innings in which a pitcher does not allow a single hit. The Venn diagram between shutouts and no-hitters is a large circle mostly overlapping with a smaller circle: no-hitters can allow runs if batters reach on errors or pitchers walk too many batters. Most no-hitters are complete games, although MLB’s most recent no-hitter was a combined no-hitter thrown on by , , and . Only three postseason no-hitters have ever been thrown:

A perfect game is a game of nine innings or more in which no opposing batter safely reaches base. Thus, no walk, hit, hit batsman, catcher’s interference, fielder’s obstruction, fielding error, or uncaught third strike may allow any batter to reach base. As a result of a 1991 rule changes, a previously perfect game spoiled in extra innings does not count. Only twenty-four perfect games have officially been pitched in MLB history. No one has ever pitched more than one, and ’s in the 1956 World Series is the only one in postseason history. threw the most recent perfect game on .

A perfect game, by definition, is a no-hitter, but not necessarily a shutout, although so far, they all have been. The “ghost runner” in extra-inning regular-season games does not spoil a perfect game, even if he advances due to such occurrences as sacrifice flies or fielding errors, so a pitcher could at least theoretically pitch a perfect game he still loses. However, there has never been an official extra-inning perfect game, so this has never happened. (I can almost guarantee that it will if any Los Angeles Angels pitcher ever manages to carry a perfect game into extra innings. If any team can find a way to lose a game in which their players do something incredible and historically unprecedented, it’s the Angels. I list two cases of games that were perfect until extra innings below. I also list unofficial perfect games the umpires themselves subsequently admitted they spoiled with bad calls below.)

Here are all twenty-four official MLB perfect games. FS stands for Final Score, PC for Pitch Count, and K for Strikeouts. Hall of Famers are italicized.

| MLB Official Perfect Games | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitcher Team |

Opposing Starter Team |

Date | FS | PC | K | |||||

Worcester Ruby Legs |

Cleveland Blues |

1880-06-12 | 1–0 | 5 | ||||||

Providence Grays |

Buffalo Bisons |

1880-06-17 | 5–0 | 2 | ||||||

Boston Americans |

Philadelphia Athletics |

1904-05-05 | 3–0 | 8 | ||||||

Cleveland Naps |

Chicago White Sox |

1908-10-02 | 1–0 | 74 | 3 | |||||

Chicago White Sox |

Detroit Tigers |

1922-04-30 | 2–0 | 90 | 6 | |||||

New York Yankees |

Brooklyn Dodgers |

1956-10-08 | 2–0 | 97 | 7 | |||||

Philadelphia Phillies |

New York Mets |

1964-06-21 | 6–0 | 90 | 10 | |||||

Los Angeles Dodgers |

Chicago Cubs |

1965-09-09 | 1–0 | 113 | 14 | |||||

Oakland Athletics |

Minnesota Twins |

1968-05-08 | 4–0 | 107 | 11 | |||||

Cleveland Indians |

Toronto Blue Jays |

1981-05-15 | 3–0 | 102 | 11 | |||||

California Angels |

Texas Rangers |

1984-09-30 | 1–0 | 94 | 10 | |||||

Cincinnati Reds |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

1988-09-16 | 1–0 | 102 | 7 | |||||

Montreal Expos |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

1991-07-28 | 2–0 | 96 | 5 | |||||

Texas Rangers |

California Angels |

1994–07–28 | 4–0 | 98 | 8 | |||||

New York Yankees |

Minnesota Twins |

1998-05-17 | 4–0 | 120 | 11 | |||||

New York Yankees |

Montreal Expos |

1999-07-18 | 6–0 | 88 | 10 | |||||

Arizona Diamondbacks |

Atlanta Braves |

2004-05-18 | 2–0 | 117 | 13 | |||||

Chicago White Sox |

Tampa Bay Rays |

2009-07-23 | 5–0 | 116 | 6 | |||||

Oakland Athletics |

Tampa Bay Rays |

2010-05-09 | 4–0 | 109 | 6 | |||||

Philadelphia Phillies |

Florida Marlins |

2010-05-29 | 1–0 | 115 | 11 | |||||

Chicago White Sox |

Seattle Mariners |

2012-04-21 | 4–0 | 96 | 9 | |||||

San Francisco Giants |

Houston Astros |

2012-06-13 | 10–0 | 125 | 14 | |||||

Seattle Mariners |

Tampa Bay Rays |

2012-08–15 | 1–0 | 113 | K | |||||

New York Yankees |

Oakland Athletics |

2023-06-28 | 11–0 | 99 | 9 | |||||

Baseball Reference says Barker threw 102 pitches in his perfect game; Baseball Almanac says 103. Likewise, BR says Browning threw 101 and BA says 102. Finally, BR says Martínez threw 96 and BA says 95. One of these days, if I feel especially bored, I may review all three videos and see which is correct.

The Rangers and Angels are the only teams to throw perfect games against each other (in the same ballpark, at that). The Yankees threw the only consecutive perfect games (strangely, in back-to-back years, and both by pitchers named David), while the Dodgers and Rays had consecutive perfect games thrown against them (the latter also in back-to-back years).

Honorable mentions:

- On 1908-07-04, the New York Giants’ lost a perfect game against the Philadelphia Phillies on a 2–2 count in a perfect game when he hit the twenty-seventh batter, opposing pitcher George McQuillan. He ulimately won the game 1–0 in ten innings. However, umpire Cy Rigler later admitted that he had miscalled a strike, meaning that Wiltse’s game should’ve been perfect. Wiltse later recalled, “Every time I saw Charlie Rigler after that he gave me a cigar. He admits [the disputed ball] was one of the pitches he missed.” Wiltse’s game remains arguably the greatest extra-inning no-hitter in MLB history; three others went into extras, and they all lasted ten innings.

- The 1991 rule change retroactively removed perfect status from a 1959-05-26 game in which the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Harvey Haddix threw 12⅔ perfect innings against the Milwaukee Braves before subsequently losing it to an error by Pirates third baseman Don Hoak. Pittsburgh then went on to lose the game when Joe Adcock hit an apparent home run (later ruled a ground-rule double due to a rare baserunning mistake by Hank Aaron, who did not see the ball clear the first fence). Haddix handled the decertification of his perfect game a lot more gracefully than I would’ve, saying only, “It’s OK. I know what I did.” Milwaukee’s Bob Buhl, at a banquet for the game’s 30th anniversary, subsequently admitted to having stolen signals from catcher Smoky Burgess and relayed them to Milwaukee’s hitters with a towel. Aaron was the Braves’ only batter who refused to take the signals (which gives his own response to the Houston Astros’ 2017 sign-stealing scandal, “I think whoever did that should be out of baseball for the rest of their lives,” a lot more force). Despite this, Adcock had Milwaukee’s only hit; Aaron had been intentionally walked. Arguably the only greater effort by a losing pitcher in MLB history was Bob Hendley’s in Koufax’s perfect game: Hendley gave up one hit and no earned runs and still got the L.

- On 1995-06-03, the Montreal Expos’ (no relation to Dennis) gave up a double to the San Diego Padres’ Bip Roberts in the bottom of the tenth inning; Montreal manager Felipe Alou then brought in reliever Mel Rojas. After a wild pitch, Rojas retired the next three batters, and Montreal won the game 1–0. Martínez displayed a lot more aplomb than I would’ve in his shoes, saying, “We went on to win, but according to the rulebook, I could not be given credit for a perfect game, even though I had gone nine perfect innings. Reporters afterward told me that the last person to lose a perfect game in extra innings was Harvey Haddix. I really wasn’t that upset about losing a perfect game according to a technicality. Everyone with the Expos thought I received some vindication.” Alou responded, “This was the best answer Pedro could give… I’m not surprised that he threw this kind of game.”

Unofficially, retired twenty-eight consecutive batters on 2010-06-02. How? Umpire Jim Joyce ruled that the Cleveland Indians’ Jason Donald had safely reached first. Galarraga handled this far more gracefully than I would’ve, saying Joyce “probably feels more bad than me. Nobody’s perfect. Everybody’s human. I understand. I give the guy a lot of credit for saying, ‘I need to talk to you.’ You don’t see an umpire tell you that after a game. I gave him a hug.”

Hall of Fame closer Mariano Rivera said:

“It happened to the best umpire we have in our game. The best. And a perfect gentleman… It’s a shame for both of them, for the pitcher and for the umpire. But I’m telling you he is the best baseball has, and a great guy. It’s just a shame.”, who lost a 1972-09-02 bid for a perfect game (, SABR) when umpire Bruce Froemming called two borderline pitches to 27th batter Larry Stahl balls, told Galarraga:

“I feel for you. There have been only 20 perfect games in the history of baseball. The umpire situation was the same one I had; they blew it. At least I had the satisfaction of getting a no-hitter. You don’t. I feel for you; you pitched a tremendous game. At least you have the satisfaction of the umpire saying he was sorry. But that doesn't help your situation as far as a perfect game.”(Pappas subsequently retired the twenty-eighth batter, preserving the no-hitter. He also reacted a lot more like I suspect I would’ve in his shoes: he was initially furious; then, after the game, he publicly gave Froemming the benefit of the doubt; but over the decades, Froemming’s refusal to second-guess his own calls increasingly infuriated Pappas.)

Both Galarraga and Joyce received praise for their handling of the situation from sources up to and including President Barack Obama, who said their conduct “showed something about sportsmanship that you don’t see enough of in America today.” Some two weeks after the game, Joyce was voted MLB’s best umpire with 53% of votes; one player said:

“The sad thing…is, Jim Joyce is seriously one of the best umpires around… He always calls it fair, so players love him. Everyone makes mistakes, and it’s terrible that this happened to him.”Joyce and Galarraga have both called for Galarraga’s game to be retroactively certified as a perfect game, but thus far, baseball commissioners Bud Selig and Rob Manfred have refused calls to do so. However, it was likely a major factor in MLB’s subsequent implementation of the instant replay system.

Perfect game win-loss records for franchises with at least two (using cumulative scores as tiebreakers):

- New York Yankees: 4–0 (score: 23–0)

- Philadelphia Phillies: 2–0 (score: 7–0)

- Cleveland Naps/Indians/Guardians: 2–0 (score: 4–0)

- Chicago White Sox: 3–1 (score: 11–1)

- Philadelphia/Oakland Athletics: 2–2 (score: 8–14)

- Texas Rangers: 1–1 (score: 4–1)

- California/Los Angeles Angels: 1–1 (score: 1–4)

- Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers: 1–3 (score: 1–5)

- Minnesota Twins: 0–2 (score: 0–8)

- Tampa Bay Rays: 0–3 (score: 0–10)

9+ inning perfect games in other top-level professional sports leagues:

- Nippon Professional Baseball has had sixteen official perfect games in its history:

- 1950-07-28: Hideo Fujimoto (藤本 英雄, Yomiuri Giants) vs. Nishi-Nippon Pirates, 4–0, 7 K

- 1955-06-19: Fumio Takechi (武智 文雄, Kintetsu Pearls) vs. Daiei Stars, 1–0, 6 K

- 1956-09-19: Yoshitomo Miyaji (宮地 惟友, Kokutetsu Swallows) vs. Hiroshima Carp, 6–0, 3 K

- 1957-08-21: Masaichi Kaneda (金田 正一, Kokutetsu Swallows) vs. Chunichi Dragons, 1–0, 10 K

- 1958-07-19: Sadao Nishimura (西村 貞朗, Nishitetsu Lions) vs. Toei Flyers, 1–0, 6 K

- 1960-08-11: Gentarō Shimada (島田 源太郎, Taiyo Whales) vs. Osaka Tigers, 1–0, 3 K

- 1961-06-20: Yoshimi Moritaki (森滝 義巳, Koktetsu Swallows) vs. Chunichi Dragons, 1–0, 4 K

- 1966-05-01: Yoshirō Sasaki (佐々木 吉郎, Taiyo Whales) vs. Hiroshima Carp, 1–0, 7 K

- 1966-05-12: Tsutomu Tanaka (田中 勉, Nishitetsu Lions) vs. Nankai Hawks, 2–0, 7 K

- 1968-09-14: Yoshiro Sotokoba (外木場 義郎, Hiroshima Toyo Carp) vs. Taiyo Whales, 2–0, 16 K

- 1970-10-06: Koichiro Sasaki (佐々木 宏一郎, Kintetsu Buffaloes) vs. Nankai Hawks, 3–0, 4 K

- 1971-08-21: Yoshimasa Takahashi (高橋 善正, Toei Flyers) vs. Nishitetsu Lions, 4–0, 1 K

- 1973-08-10: Soroku Yagisawa (八木沢 荘六, Lotte Orions) vs. Taiheiyo Club Lions, 1–0, 6 K

- 1978-08-31: Yutaro Imai (今井 雄太郎, Hankyu Braves) vs. Lotte Orions, 5–0, 3 K

- 1994-05-18: Hiromi Makihara (槙原 寛己, Yomiuri Giants) vs. Hiroshima Toyo Carp, 6–0, 7 K

- 2022-04-10: Rōki Sasaki (佐々木 朗希, Chiba Lotte Marines) vs. Orix Buffaloes, 6–0, 19 K

Notes:

- As far as I know, all three Sasakis are unrelated.

- In Makihara’s game, the Giants dropped a foul fly ball, which was scored as an error, but Makihara went on to retire the batter, so he kept his perfect game.

- Rōki was the youngest pitcher to throw a perfect game in NPB history; he is also the only pitcher I know of to have fanned more than two-thirds of the batters he faced in a perfect game. At one point he struck out 13 straight batters, which is an all-time NPB record. He was also perfect in the next eight innings he threw on 2022-04-16, but he was removed after having thrown 102 pitches in what at the time was a scoreless tie (Chiba lost the game 1–0 in extra innings).

- The World Baseball Softball Confederation also recognizes a 2007-11-01 Japan Series-clinching 1–0, seven-strikeout victory by the Chunichi Dragons’ Daisuke Yamai (山井 大介) and Hitoke Iwase (岩瀬 仁紀) over the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters as a combined perfect game; it is the only combined perfect game in top-level pro baseball history to span a regulation nine innings.

- The Chinese Professional Baseball League has had one, thrown by Ryan Verdugo on 2018-10-07.

The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League had five perfect games in its history (1943–1954):

- 1944-07-29: Annabelle “Lefty” Lee (Minneapolis Millerettes) vs. the Kenosha Comets

- Later named Annabelle Harmon; her nephew, MLB pitcher , called her “the best athlete in our family, including me” and credited her with teaching him to play.

- 1945-07-06 Carolyn Morris (Rockford Peaches) vs. the Fort Wayne Daisies

- 1947-08-18: Doris “Sammye” Sams (Muskegon Lassies) vs. the Fort Wayne Daisies

- Sams, a superb two-way player, had a career .290 batting average (sixth-best in league history) and .368 slugging%; she also set a league record in 1952 with twelve home runs. Unsurprisingly, she was twice selected as its Player of the Year.

- 1951-07-21: Jean Faut (South Bend Blue Sox) vs. the Rockford Peaches

- 1953-09-03: Jean Faut (South Bend Blue Sox) vs. the Muskegon Lassies

- Faut, also an excellent two-way player (.243 average, .299 slugging%), was the only pro baseball player ever to throw two perfect games; she ended her career with a 140–64 record and 1.23 ERA, the lowest for any AAGPBL pitcher with at least 500 IP. She was second in wins only to Helen Nicol Fox (163), and third on its career strikeouts list with 913. She was also a two-time Player of the Year; she and Sams were the only players so honored.

Baseball Almanac has more.

A Maddux, named for Hall of Famer , is a complete-game shutout thrown in under 100 pitches. 1988 was the first year of pitch count tracking, so they’re not officially tracked before then, but some games have since been determined to qualify for the accomplishment.

Greg Maddux became the eponym because he threw a record thirteen in his twenty-three-year career (, , , , , , , , , , , , ). Runner-up threw seven (, , , , , , ). Maddux (1998) and Smith (1991) also share the single-season record, with three apiece. Interestingly, both were Atlanta Braves pitchers for much of their careers, though not at the same time (and indeed, Smith threw all seven of his for the Pittsburgh Pirates). Two other weird coincidences: Maddux and Smith both threw Madduxes on 1994-08-11, that season’s last day of baseball due to a players’ strike. (My birthday is the 12th. Worst. Birthday present. Ever.)

Thirteen Madduxes since 1988 were no-hitters; at least five (in bold and italics) were also perfect games. Baseball Almanac has also retroactively found five pre-1988 perfect games to have been Madduxes.

(Intro to hitting stats TK)

Let’s start with one of Ohtani’s less eye-catching (but still record-setting) accomplishments. Before 2024, no player who had hit fifty or more home runs had stolen more than twenty-four bases in the same season. (1955) and (2007) shared the record. Similarly, had the high count for home runs in a season with at least fifty stolen bases: seventy-three stolen bases, forty-one home runs.

There’s a lot of reasons for this, starting with the obvious one that stealing bases is an achievement of speed, while hitting home runs is an achievement of power. A perhaps slightly less obvious one is that these two goals are mutually exclusive. Every single home run a player hits is a chance they will not get to steal a base.

Before the game on , Ohtani had forty-eight home runs and forty-nine stolen bases that season.

When it ended, he didn’t have fifty home runs, nor did he have fifty stolen bases.

He had fifty-one home runs and fifty-one stolen bases.

In all, he went six for six, with five extra-base hits, seventeen total bases, and ten RBI. The Dodgers clinched their playoff berth with a 20–4 victory. Miami Marlins manager also deserves credit for the respect he showed both Ohtani and the game of baseball. In the top of the seventh inning, Ohtani was four for four with a home run, two doubles, and two stolen bases, and Los Angeles led 11–3. Schumaker was asked about intentionally walking Ohtani. He responded, “Fuck that. Too much respect for this guy for that shit to happen.”

After the game, he called the idea of an intentional walk:

“a bad move… karma-wise, baseball god-wise. You go after him and see if you can get him out. Out of respect for the game, we’re gonna go after him. He hit the home runs; that’s just part of the deal.”

(File this quote away in your mind – we’ll be returning to it later.)

He also called Ohtani “the most talented player” he’d ever seen (high praise indeed from of future Hall of Famer ) and said Ohtani was:

“doing things that I’ve never seen done before…. If he has a couple more of these peak years, he might be the best ever to play the game.… It was a good day for baseball, a bad day for the Marlins.”

The Marlins’ audience clearly understood they were witnessing history as well: even though their team was being blown out, they responded to his accomplishments with enthusiastic applause. (This is hardly unprecedented; visiting pitchers often get standing ovations from home crowds after throwing perfect games.)

In that game, Ohtani became the first:

MLB player since RBI have been tracked to have:

across an entire career. And he did it all in one game.

Ohtani ended the season with 54 home runs and 59 stolen bases, and he was only caught stealing four times that entire season. In fact, he isn’t just the only member of MLB’s 50–50 club. He’s also the only member of its 45–45 club. Let’s break down how astonishing this accomplishment is:

Just two other players have hit at least fifty home runs and stolen at least fifty bases in separate years:

Which makes for a great trivia question: “Who is the only Major League Baseball player besides Barry Bonds and Shōhei Ohtani to have hit at least fifty home runs and stolen at least fifty bases in any (not necessarily the same) season?” (I might’ve guessed the late, dearly lamented , who hit a respectable 297 career home runs, but never more than 28 in a season [1986, 1990].)

The 40–40 club has only five other members, and no one, including Ohtani, has entered it twice:

Two hit at least forty home runs the same year they stole at least forty-five bases:

One hit at least forty-five home runs the same year he stole at least forty bases:

The other two hit forty-two home runs the same year they stole forty bases:

(Canseco, the first to do so, correctly predicted that he would accomplish the feat in 1988; ironically, he mistakenly assumed he would be the sixth or seventh player to do so. was subsequently quoted as saying, “Hell, if I’d known 40–40 was going to be a big deal, I’d have done it every year!”)

Icing on the cake: Ohtani got to 40–40 in 21 fewer games than any of his predecessors. And he did it with a walk-off grand slam.

Perhaps most importantly, Ohtani founded the 50–50 club while probably dozens of MLB pitchers who were in the midst of rehabbing from Tommy John surgery. One of those pitchers is named Shohei Ohtani. Because, as most people who read this were already aware, I may have deliberately buried the lede a bit.

We’re obviously going to focus on that more, but first, I want to emphasize that this is what he did while he was injured. Just mind-boggling.

Ohtani isn’t just a speed demon who can hit to all corners of the field. He also pitches a bit. If you’re European, imagine and being the same player and you’ll get an idea of how rare this is. (Substitute and if you’re a bit younger, and and if you’re a lot younger.)

Ohtani is the first player to have excelled to this degree at both hitting and pitching since Hall of Famer retired from the Negro Leagues in 1945. He’s also by far the most famous player to have done so since one , and Ohtani has arguably already outdone the Bambino on numerous counts. Babe was an excellent pitcher and an incredible hitter, but he mostly focused on pitching with the Red Sox and on hitting with the Yankees; he was also a middling baserunner who got worse as he aged. Ohtani has both hit and pitched fairly consistently despite some injuries, and as we’ve seen, he’s also a superb baserunner.

On , Ohtani founded another, even more remarkable 50–50 club, becoming MLB’s first player to strike out 50 batters and hit 50 home runs in the same season. (Bonus: He passed both milestones in the same game – and pitched five no-hit innings at that. Remarkably, Los Angeles’ bullpen somehow lost the game anyway.)

He’s also the first modern player to lead his league in pitching and offensive statistics in one season (2022): as a pitcher, he led the AL in strikeouts per innings pitched (11.87); as a hitter, he had the highest exit-velocity home run that season (111.9 mph); and as a baserunner, he led MLB with a home-to-first average time of 4.09 seconds. And 2022 was his weakest season since he spent most of 2020 recovering from an injury!

Needless to say, he’s won countless awards, including but hardly limited to:

He’s only the second player to have been named MVP in both leagues (following , who won the 1961 NL MVP as a Cincinnati Red and the 1966 AL MVP as a Baltimore Oriole). Ohtani won all four MVPs unanimously, which is unprecedented in at least two ways:

He’s also led either the AL or NL (and sometimes both) in several important statistics in up to three seasons since 2021 (his first full MLB season with no major injuries):

| Shōhei Ohtani’s first-place season statistics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count for | LA Angels | LA Dodgers | |||||

| MLB | AL/NL | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Win probability added (WPA) | 3 | 3 | MLB | MLB | MLB | ||

| On-base plus slugging (OPS) | 1 | 3 | MLB | NL | NL | ||

| Slugging percentage (SLG) | 1 | 3 | MLB | NL | NL | ||

| Total bases (TB) | 1 | 3 | AL | NL | MLB | ||

| Reference-weighted runs batting (Rbat+) | 1 | 3 | MLB | NL | NL | ||

| Wins above replacement (WAR) | 0 | 3 | AL | AL | NL | ||

| Extra-base hits (EBH) | 0 | 3 | AL | NL | NL | ||

| Base-out runs added (RE24) | 0 | 3 | AL | NL | NL | ||

| Reference-weighted on-base average (rOBA) | 0 | 3 | AL | NL | NL | ||

| Runs scored (R) | 2 | 2 | MLB | MLB | |||

| Home runs (HR) | 0 | 2 | AL | NL | |||

| On-base percentage (OBP) | 0 | 2 | AL | NL | |||

| Intentional base on balls (IBB) | 0 | 2 | AL | NL | |||

| Power-speed number (PSN) | 0 | 2 | AL | NL | |||

| At-bats per home run (AB/HR) | 0 | 2 | AL | NL | |||

| Triples (3B) | 1 | 1 | MLB | ||||

| Fielding percentage (Fld%) | 1 | 1 | MLB | ||||

| Runs batted in (RBI) | 0 | 1 | NL | ||||

| Strikeouts per nine innings pitched (SO9) | 0 | 1 | AL | ||||

Clearly, his 2022 season lagged behind the other four, and of those four, note that the two seasons he led in IBB were the two he didn’t lead in home runs. This is not coincidental.

But is Ohtani a good enough pitcher to win a Cy Young Award someday? Perhaps. Let’s compare his last five years to ’s. (Remember, in 2024, Sale won the Triple Crown and the NL Cy Young Award.)

| 2021–25 pitching stats: Sale & Ohtani | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitcher | IP | W–L | ERA | SO | SO9 |

| Chris Sale | 454⅓ | 36–14 | 2.95 | 572 | 11.331 |

| Shōhei Ohtani | 475⅓ | 35–17 | 2.84 | 604 | 11.436 |

Not all their stats are that similar, but it’s kind of spooky how close these are. If I saw those numbers devoid of context, I’d probably assume they were different five-year spans from the same pitcher.

Baseball is effectively a series of pitcher-hitter interactions. Since the National League adopted the designated hitter in 2022, most players have only had chances to do one or the other. Coincidentally, in 2022, Ohtani faced 666 batters (BF) and made 660 plate appearances (PA). Neither of those is especially noteworthy on its own, but that sums up to a career-high 1,326 chances to affect a game’s score, which, for lack of a better term, I’ll just call total plays (TP). By contrast, the Miami Marlins’ led MLB that year in BF (886), and the Texas Rangers’ led MLB that year in PA (724). With both leagues now using the DH and no other pitchers batting for themselves, Ohtani led MLB in TP by 450.

So, how remarkable are 1,326 TP? Well, ’ 778 PA in 2007 are the single-season record, so you’ll have to pitch a lot to exceed 1,326 TP. The last player to do so was in 1980, and narrowly at that: 1,221 BF, 111 PA, 1,332 TP. (He was also on fire as a pitcher, leading MLB with 162 ERA+, 2.42 FIP, 286 strikeouts, and 10.2 pWAR. Unsurprisingly, he won 1980’s NL Cy Young Award. His hitting stats, though, were .188/.190/.198, for −0.1 nWAR – respectable stats for a pitcher, but nothing to write home about. He still led MLB in overall WAR with 10.1; runner-up had 9.4.)

Legendary Atlanta Braves knuckleball pitcher exceeded them both in 1979 far more comfortably, with 1,570 TP from 134 PA (with a respectable 0.4 nWAR; his .195/.213/.244 hitting stats are respectable by pitchers’ standards and actually almost legendary by 39-year-old pitchers’ standards) and 1,436 BF (with an MLB-best 7.4 pWAR); his 7.7 WAR was good for fifth-best in MLB. (In 1978, he’d led MLB in WAR outright with 10.4, outstripping runner-up [and AL Cy Young winner] by 0.8. Since knuckleballs are unusually slow, knuckleballers often have unusually long careers; Niekro played his last MLB game at forty-eight, making him MLB’s tenth-oldest player ever. His career total of 22,677 BF is a modern record; all-time, only [29,565 in 1890–1911], [25,415 in 1875–1892], and [23,415 in 1907–1927] faced more.)

Carlton again came close to exceeding 1,326 TP in 1982 (1,302 TP, 1,193 BF, 109 PA) and 1983 (1,288 TP, 1,183 BF, 105 PA), but that’s all, and since 1980, only a few other players have even come within 100:

Naturally, Ohtani’s 45.5 WAR from 2021–2025 led MLB; only (41.8) even came close, with (32.2) a distant third. Is it any surprise that Ohtani has been a unanimous MVP for ?

On , Ohtani faced Yankees closer in the bottom of the eighth inning and struck out on a 100 mph sinker. The replay clearly shows how impressed he was. He’d been experimenting with a sinker since May that year and had gotten its velocity up to 100 mph, but it didn’t really have the sink a good sinker needs, nor did he have the command he wanted over it. According to his teammate , Ohtani went to the bullpen the very next day, pulled up Holmes’ movement numbers, and went to town trying to match them.

Ohtani next pitched on against the Houston Astros. He struck out five batters in eight innings, giving up a single run on six hits. After a 100 mph sinker sailed by for strike three, McCormick showed the same expression that Ohtani had shown after Holmes’ sinker. Ohtani threw his retooled sinker twenty times that day. The results are clear. (“VB” and “HB” respectively stand for ”Vertical Break” and “Horizontal Break”.)

| Sinker Comparison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitcher | Batter | Date | mph | rpm | VB | HB |

| Ohtani | Blue Jays | 2022-08-27 | 97.1 | 1935 | 5” | 15” |

| Holmes | Ohtani | 2022-08-31 | 99.7 | 2215 | 4” | 18” |

| Ohtani | McCormick | 2022-09-03 | 99.7 | 2092 | 8” | 20” |

As of 2022-09-02, ’s sinker had the highest horizontal break in MLB with 19.3”. Ohtani’s was 20”. Furthermore, of the top twenty horizontal-breaking sinkers in MLB, ’s had the highest velocity at 96.6 mph. Ohtani’s was 99.7. In short, he took a single bullpen session to learn to throw a new pitch better than everyone else in Major League Baseball.

Who else does anything even remotely like this?

And, again, injuries have curtailed his pitching over his time in MLB; who knows how much better he’ll get if he avoids them. He might’ve given us a preview in 2025’s NL Championship Series’ , wherein he went where no one except callow adolescents ever even imagined going before. In that game, Ohtani:

His twelve total bases in that game ties for seventh-highest in any playoff game in history:

| Most Total Bases in One Playoff Game | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| # | Player | Game | TB |

| 1. | 14 | ||

| 3. | 13 | ||

| 7. | 12 | ||

(And, of course, I’ve gotten ahead of myself – we’ll discuss World Series Game 3 below.)

Numerous sportswriters immediately proclaimed it the greatest single-game performance by a single athlete in not just baseball history, but sports history. In short, it’s hardly a hot take to call Ohtani an athlete of historically unprecedented talent and skill.

Ohtani’s NLCS Game 4 isn’t the only feat of its kind in baseball history, but it arguably still stands out from the others. I read a comment from someone to the extent that they’d had a player strike out ten batters and hit three home runs in MLB: The Show a few days before NLCS Game 4, and they’d chuckled to themselves about how unrealistic a feat it was. But it wasn’t unrealistic for Ohtani, since he’d already had a ten-strikeout game in which he’d hit two homers on . There are several reasons NLCS Game 4 is more impressive: it was a postseason game, it featured one more home run, and Ohtani was more dominant on the mound – in the earlier game, he’d allowed one run on four hits. Until Ohtani, no one had ever struck out at least ten batters and hit at least two home runs in two games, and only five pitchers before him had even done it in one game:

(Fun fact: Greinke was the starting pitcher of the game in which Bumgarner hit two home runs, and despite the latter’s efforts, he didn’t get the win – poor run support from his teammates and a bullpen collapse contributed to San Francisco losing the game. On the other hand, since it was an Opening Day game, and Bumgarner went 2 for 2 with a walk, he finished the day with 1.000/1.000/4.000 hitting stats for the season. Bumgarner was always a better-than-average hitting pitcher, hitting a career .172/.232/.292 with 19 HR and 65 RBI. Perhaps not as impressive as Wes Ferrell’s .280/.351/.446 or Don Newcombe’s .268/.336/.361, but in the same ballpark as Orel Hershiser’s .201/.230/.242, Fernando Valenzuela’s .200/.205/.261, Tom Glavine’s .186/.244/.210, Greg Maddux’s .171/.191/.205, Rick Wise’s .195/.228/.308, Warren Spahn’s .194/.234/.287, and Jack Harshman’s .179/.294/.344.)

A few slugging accomplishments by pitchers deserve further attention:

Until Ohtani, only two pitchers had ever hit three home runs in one game:

Now technically, Ohtani only pitched six innings and was officially considered the designated hitter when he hit his third homer, while Tobin and Hecker pitched complete games. But then, Hecker allowed one earned run on four hits, and Tobin committed a fielding error and allowed three earned runs on five hits, while Ohtani committed no fielding errors and allowed no runs on two hits. Also, Ohtani’s game was against the team with the best record in baseball and secured the Dodgers’ World Series berth against the team with the best record in the American League (which, of course, they went on to win), while the Louisville Colonels finished 1886 fourth in the American Association with a 66–70–2 record, and the Braves finished 1942 seventh in the National League with a 59–89 record. We’ll call it a draw.

The Atlanta Braves’ hit two grand slams in a . That remains the franchise record and ties with for the MLB record. His nine RBI in a single game are also the franchise record.

(Famously, the Braves made their pitchers take batting practice, so they were rarely guaranteed outs.)

I intend in no way to diminish any of the above achievements, nor Ohtani’s achievements in the NLCS Game 4. However, while Tobin hit well enough to be used as a pinch hitter (in fact, he’d hit a pinch-hit homer ), none of the above pitchers except arguably Hecker ever hit on Ohtani’s level (and only Gibson pitched on it). Put another way, Ohtani’s third-best game is so much better than Tobin, Wise, Cloninger, or even Gibson or Hunter’s third-best games (to the extent that… what even are Ohtani’s second and third-best games? There’s plenty of room for debate) that they’re hardly even worth comparing. (And with records of Hecker’s career being so scant, we can’t be sure what his second and third-best games were.)

There’s also the matter of stakes. Ohtani’s game clinched the pennant against the team with the best record in baseball. Of the games above, only Gibson’s game had comparable stakes, since it was in the World Series.

One final accomplishment that might be worth considering: ’s in the 1956 World Series, which is another accomplishment with comparable stakes. I never expect to see another World Series perfect game as long as I live (then again, Yoshinobu Yamamoto might surprise us someday). That said, Larsen might’ve pitched better, but he went 0 for 2 at the plate that day, so was it really a perfect game?

OK, I’m being somewhat facetious, but I’m making a serious point. Ohtani is performing at an elite level as both a hitter and a pitcher to an extent that was previously considered impossible. A new rule allowing starting pitchers to become designated hitters after being removed as pitchers is informally called “the Ohtani rule”. That speaks volumes: what other pitchers ever hit well enough for that to even be a consideration? We’ve seen better pitchers than Ohtani, better hitters than Ohtani, better baserunners than Ohtani, but no one else has done even the first two at such an elite level, much less all three.

And this is so historic – and it’s so easy to explain why it’s historic – that even people who never cared about baseball before are taking notice, much like Michael Jordan, Michael Phelps, Tiger Woods, and the Williams sisters had broad appeals that extended far beyond the usual basketball, swimming, golf, and tennis aficionados. Plus, it helps that Ohtani is just immensely fun to watch, with a joy for the game that’s simply infectious.

(Larsen’s offensive performance during his perfect game was somewhat out of character for him: he was a career .242/.291/.371 hitter with fourteen homers and an 81 OPS+ in 653 plate appearances, roughly seventy-five of them as a pinch-hitter. However, his bat tended to go quiet in October: he hit .111/.333/.111 in the postseason.)

, one of the greatest and most versatile basketball players of all time, has never finished a season in the top ten in all three of the sport’s most important statistics: points, rebounds, and assists. (In fact, although he is the career rebound leader among active players, he has never finished a season in the top ten.) Neither did , who led the NBA in points year after year and remains its all-time leader in points per game, but was only a middling rebounder. It’s difficult to make 1:1 comparisons to baseball, but in 2022, Ohtani finished top ten in three major offensive statistics (4th in home runs, 6th in slugging%, 6th in OPS) and first or second place in three major pitching statistics (1st in SO/9IP, 2nd in pitching WAR, 2nd in FIP).

Quick. Name the only player in MLB history to hit at least 500 home runs and post a career ERA under 2.00 and ERA+ above 250.

…

Sorry, “” is not the correct answer. His career ERA is 2.28, and his career ERA+ is 122. Those are respectable numbers, but I’ll print the correct answer below the next table.

Most people seem to think Ohtani and the Bambino are the only two-way players in MLB’s history. Most people are egregiously wrong. In fact, Ohtani arguably isn’t even its only active two-way player: has pitched 996 innings and has logged 96 innings without a single error as an outfielder. Lorenzen has averaged one home run per nineteen career at-bats (beating 2025’s MLB average 28.967 AB/HR by almost 10) without calling the Colorado Rockies’ notoriously hitter-friendly Coors Field his home field. The Rockies just signed him. If they have even an ounce of sense, they’ll play him in the outfield on days when he’s not pitching and let him hit even when he is. (Heck, I’ll go further: if they have any sense, they signed him more for his bat than for his arm. Coors Field is so hitter-friendly that their best hope to actually win games is to out-hit their opponents, and Lorenzen’s bat could raise their dinger count substantially.)

In over 150 years of American professional baseball, dozens of players have achieved major-league success as both hitters and pitchers; at least thirteen two-way players are Hall of Famers. (Arguably, seventeen or more are, and at least one of them – the correct answer to our above trivia question, as it turns out – will surprise you.) Before we meet some of them, a few notes:

√fWAR·rWAR when both were positive, and the arithmetic mean of fWAR+rWARFor players who played mostly or entirely in the Negro Leagues and/or Latin American leagues, I also used Seamheads’ WAR calculations (sWAR). In some cases, I used sWAR exclusively; in others, I used a geometric mean of ³√fWAR·rWAR·sWAR if all three values were positive or an arithmetic mean of fWAR+rWAR+sWAR

3 if they weren’t. I was especially likely to weight the three WAR values together for players who:

(Seamheads calls its own totals gWAR, for “Baseball Gauge Wins Above Replacement”; I opted to use sWAR to avoid confusion with “Goose Wins Above Replacement”, found in the pitching stats above.)

I’ve chosen to list players that meet at least one of two definitions:

I relaxed requirements for Negro League players proportionally to season lengths (e.g., Dave Malarcher never threw more than eight innings in a season, but his team only played 63 games that season, which scales to a pace of 20⅔ innings in a 162-game season).

Since a replacement-level player in 1871 and a replacement-level player in 2025 are playing at vastly different skill levels, we cannot assume wins above replacement to remain constant over time. Sabermetrician Bill James notes that in baseball’s early days, “the best players were further from the average than they are now.”

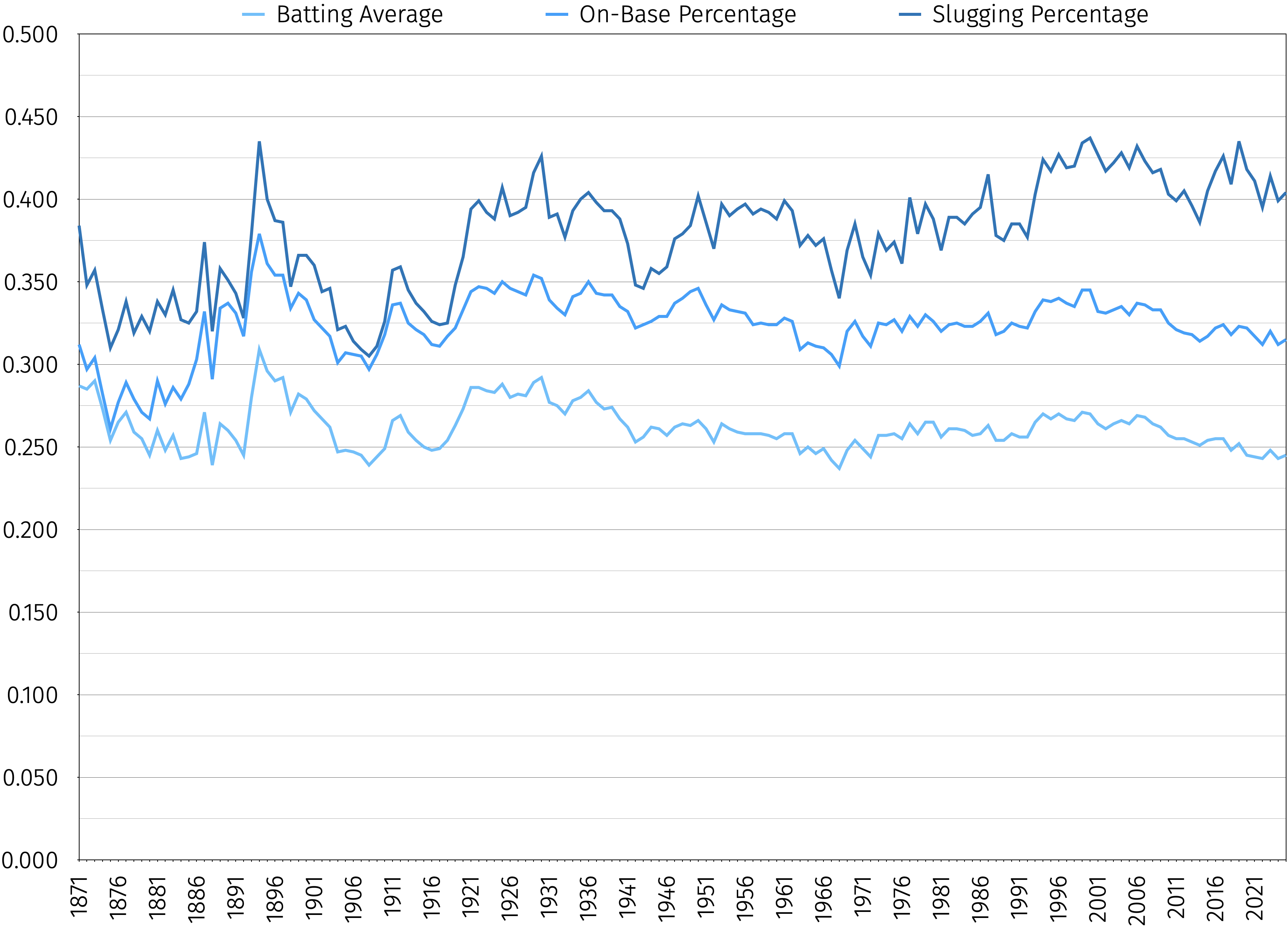

Similarly, evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould argued (Full House: The Spread of Excellence from Plato to Darwin) that .400 batting averages disappeared due to a decline not in hitting quality, but in skill differentials between players. Gould notes that league averages have remained roughly constant over time; what’s decreased has been the standard deviation of individuals’ averages, and the largest outliers with them.

If anything, I’d argue that this is a sign that modern hitting and pitching are both much better. I’ll explain in detail below (“Even and couldn’t hit .400 against modern pitching”), but the short version is: Williams and never faced or ; Gibson and never faced or ; and all eight players’ numbers improved as a result.

In short: baseball’s skill ceiling hasn’t lowered since Cobb and Gibson’s era; its skill floor has risen.

| A Brief History of Two-Way Baseball Players | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| player | from | to | pg / pwms | og / owhs | war / games | |||

| 1871-05-05 | 1878-08-31 | 347 | 2.83 | 133 | 2.62 | 50.0 | 480 | |

| 1872-04-26 | 1904-09-22 | 6 | 1.02 | 2078 | 3.72 | 52.2 | 2084 | |

| 1873-04-21 | 1877-10-06 | 157 | 3.70 | 117 | 1.76 | 29.5 | 274 | |

| 1876-05-20 | 1884-10-13 | 176 | 1.54 | 51 | 1.48 | 14.8 | 227 | |

| 1878-05-01 | 1888-10-14 | 32 | 1.64 | 824 | 1.12 | 8.8 | 856 | |

| 1878-05-17 | 1899-07 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 1878-07-15 | 1894-09-29 | 293 | 2.15 | 1579 | 2.74 | 63.6 | 1872 | |

| 1880-05-05 | 1891-08-11 | 527 | 2.65 | 151 | 0.65 | 63.3 | 678 | |

| 1881-05-02 | 1890-07-16 | 413 | 2.72 | 163 | 2.69 | 55.8 | 576 | |

| 1881-05-21 | 1887-08-16 | 100 | 1.68 | 198 | 2.95 | 11.2 | 298 | |

| 1881-08-27 | 1894-07-26 | 555 | 2.37 | 265 | 1.43 | 60.1 | 820 | |

| 1882-05-01 | 1897-07-14 | 8 | 0.90 | 1678 | 2.25 | 27.0 | 1686 | |

| 1882-05-02 | 1890-09-30 | 336 | 2.08 | 407 | 2.64 | 41.2 | 733 | |

| 1884-04-24 | 1897-10-03 | 16 | 1.00 | 684 | 3.63 | 19.4 | 700 | |

| 1884-05-01 | 1887-10-08 | 183 | 2.87 | 85 | 3.52 | 28.0 | 183 | |

| 1884-05-22 | 1894-09-24 | 15 | 1.18 | 1127 | 2.12 | 17.5 | 1142 | |

| 1884-06-20 | 1901-09-09 | 188 | 1.65 | 226 | 1.27 | 15.0 | 414 | |

| 1884-07-29 | 1896-05-14 | 251 | 2.28 | 917 | 1.83 | 37.7 | 1168 | |

| 1884-08-18 | 1891-06-15 | 140 | 1.26 | 11 | 2.50 | 9.9 | 728 | |

| 1884-09-07 | 1892-05-19 | 340 | 2.72 | 388 | 3.66 | 54.9 | 728 | |

| 1886-04-17 | 1898-08-17 | 303 | 2.16 | 39 | 0.90 | 28.5 | 342 | |

| 1886-09-10 | 1901-06-15 | 149 | 2.19 | 1089 | 3.38 | 43.8 | 342 | |

| 1888-04-21 | 1895-07-02 | 231 | 1.85 | 167 | 1.68 | 21.5 | 398 | |

| 1888-06-06 | 1892-10-14 | 168 | 3.28 | 85 | 1.64 | 25.2 | 253 | |

| 1888-09-15 | 1896-08-28 | 264 | 1.79 | 39 | 2.17 | 21.7 | 303 | |

| 1889-06-26 | 1899-06-12 | 388 | 2.65 | 185 | 2.01 | 45.3 | 601 | |

| 1891-04-11 | 1914-10-07 | 453 | 3.11 | 25 | 1.31 | 56.2 | 486 | |

| 1893-06-18 | 1896-09-26 | 115 | 1.76 | 166 | 1.24 | 9.4 | 281 | |

| 1894-04-21 | 1902-09-27 | 335 | 2.00 | 218 | 1.61 | 27.6 | 566 | |

| 1894-05-12 | 1913-08-09 | 195 | 2.01 | 684 | 1.69 | 24.5 | 923 | |

| 1894-07-14 | 1911-04-12 | 359 | 2.78 | 87 | 2.00 | 43.7 | 508 | |

| 1894-09-15 | 1918-09-02 | 57 | 2.93 | 1579 | 4.13 | 72.3 | 1872 | |

| 1895-08-15 | 1909-09-20 | 440 | 2.53 | 74 | 1.91 | 47.9 | 610 | |

| 1896-04-22 | 1913-07-17 | 141 | 1.24 | 1341 | 3.15 | 39.4 | 1529 | |

| 1897-08-27 | 1915-10-03 | 9 | 2.75 | 1371 | 5.12 | 41.6 | 1447 | |

| 1899 | 1914 | 2 | 4.62 | 472 | 6.22 | 18.5 | 474 | |

| 1900 | 1919 | 116 | 2.75 | 505 | 2.99 | 23.4 | 621 | |

| 1901-04-22 | 1913-10-04 | 427 | 2.51 | 89 | 1.04 | 41.3 | 552 | |

| 1904-04-16 | 1910-10-13 | 182 | 1.33 | 136 | 2.40 | 11.0 | 378 | |

| 1906-07-05 | 1920-07-20 | 354 | 1.69 | 63 | 1.97 | 23.8 | 466 | |

| 1907 | 1926 | 326 | 3.02 | 507 | 2.99 | 40.3 | 833 | |

| 1908-04-24 | 1918-04-31 | 302 | 1.79 | 80 | 4.72 | 21.6 | 502 | |

| 1908-08-24 | 1922-09-24 | 225 | 3.90 | 442 | 2.75 | 37.2 | 704 | |

| 1909 | 1926 | 57 | 2.51 | 964 | 3.97 | 19.4 | 1033 | |

| 1910-09-09 | 1921-09-29 | 343 | 2.53 | 52 | 1.99 | 32.7 | 595 | |

| 1911-06-02 | 1932-06-21 | 390 | 1.90 | 98 | 0.80 | 22.9 | 651 | |

| 1913-04-18 | 1923-09-30 | 242 | 3.33 | 138 | 2.35 | 25.9 | 422 | |

| 1913-04-18 | 1923-09-30 | 691 | 3.13 | 79 | 1.82 | 44.8 | 777 | |

| 1914-07-11 | 1935-05-30 | 163 | 2.60 | 2273 | 9.30 | 181.0 | 2504 | |

| 1915-06-28 | 1930-09-22 | 24 | 2.87 | 2012 | 3.56 | 55.2 | 2054 | |

| 1917 | 1935 | 4 | 4.38 | 488 | 5.25 | 19.1 | 484 | |

| 1920-05-02 | 1931 | 124 | 2.88 | 322 | 3.86 | 21.7 | 454 | |

| 1920-05-09 | 1932 | 62 | 4.26 | 277 | 1.68 | 12.8 | 339 | |

| 1920-05-09 | 1934 | 2 | 2.00 | 799 | 2.73 | 21.7 | 801 | |

| 1920-05-09 | 1937 | 23 | 1.84 | 882 | 4.54 | 25.6 | 905 | |

| 1920-05-09 | 1937 | 296 | 5.22 | 450 | 1.22 | 49.0 | 796 | |

| 1920-05-09 | 1932 | 68 | 1.29 | 1215 | 7.11 | 60.0 | 1283 | |

| 1920-05-20 | 1935 | 5 | 4.16 | 512 | 6.34 | 28.9 | 502 | |

| 1920-05-26 | 1934 | 154 | 1.99 | 154 | 4.01 | 13.6 | 308 | |

| 1920-06-05 | 1934 | 191 | 0.93 | 112 | 4.21 | 5.0 | 303 | |

| 1920-07-04 | 1938-09-04 | 236 | 4.66 | 565 | 5.89 | 59.2 | 801 | |

| 1921-04-21 | 1944-06-30 | 89 | 1.84 | 297 | 1.39 | 14.3 | 1174 | |

| 1921-07-13 | 1936 | 233 | 3.17 | 27 | 1.98 | 22.3 | 260 | |

| 1921-07-16 | 1927 | 127 | 1.86 | 88 | 4.53 | 11.4 | 215 | |

| 1922-05-07 | 1937 | 238 | 2.56 | 110 | 2.67 | 18.4 | 348 | |

| 1922-05-09 | 1946 | 49 | 3.63 | 1489 | 3.94 | 45.8 | 1538 | |

| 1923-04-29 | 1930 | 2 | 4.74 | 763 | 2.39 | 19.6 | 765 | |

| 1923-04-29 | 1932 | 312 | 4.39 | 377 | 2.45 | 54.8 | 689 | |

| 1923-04-29 | 1932 | 218 | 4.02 | 103 | 4.56 | 31.8 | 321 | |

| 1923-04-30 | 1945-08-05 | 228 | 4.73 | 855 | 4.90 | 70.5 | 1083 | |

| 1923-08-04 | 1937 | 220 | 4.27 | 34 | 1.58 | 34.0 | 269 | |

| 1925-05-01 | 1945-09-23 | 10 | 3.38 | 2190 | 5.99 | 97.3 | 2317 | |

| 1926-04-27 | 1949-09-27 | 89 | 2.84 | 297 | 1.60 | 12.3 | 384 | |

| 1927-08-15 | 1943 | 12 | 6.32 | 639 | 4.14 | 17.7 | 651 | |

| 1928-04-28 | 1946 | 279 | 4.38 | 279 | 1.27 | 43.3 | 558 | |

| 1930-04-15 | 1946-05-12 | 25 | 1.15 | 1648 | 3.38 | 42.7 | 1717 | |

| 1930-04-25 | 1946 | 153 | 3.33 | 512 | 4.20 | 33.1 | 665 | |

| 1930-04-26 | 1948 | 7 | 2.22 | 1511 | 4.51 | 68.9 | 1518 | |

| 1930-05-11 | 1948 | 340 | 2.91 | 171 | 1.88 | 27.1 | 511 | |

| 1931-05-03 | 1945-09-20 | 273 | 4.31 | 284 | 2.45 | 47.3 | 557 | |

| 1931-09-17 | 1950-07-23 | 428 | 2.65 | 206 | 0.99 | 44.0 | 716 | |

| 1932-05-16 | 1948 | 242 | 3.70 | 234 | 1.12 | 29.0 | 854 | |

| 1933-04-30 | 1948 | 228 | 3.85 | 378 | 2.87 | 30.6 | 606 | |

| 1934-07-08 | 1949-09-22 | 125 | 5.13 | 144 | 3.31 | 25.4 | 269 | |

| 1935-05-05 | 1946 | 241 | 2.34 | 220 | 1.56 | 19.9 | 461 | |

| 1936-05-23 | 1946 | 264 | 1.91 | 314 | 1.92 | 22.2 | 578 | |

| 1937-05-09 | 1946 | 223 | 4.17 | 98 | 3.44 | 30.3 | 321 | |

| 1941-04-18 | 1954-05-09 | 55 | 1.17 | 705 | 2.80 | 16.1 | 854 | |

| 1996-04-03 | 2004-10-03 | 74 | 1.23 | 56 | 1.17 | 0.9 | 126 | |

| 1999-08-23 | 2013-07-08 | 51 | 3.10 | 536 | 1.43 | 8.8 | 653 | |

| 2015-04-29 | — | 395 | 1.84 | 34 | 5.41 | 10.6 | 452 | |

| 2018-03-29 | — | 100 | 5.62 | 951 | 4.95 | 50.6 | 1033 | |

Honorable mentions:

is the correct answer to our trivia question: he had 534 home runs, a 1.52 ERA, and a 261 ERA+. Believe it or not, he’s not even the only Hall of Fame position player to have a super-low ERA: Honus Wagner actually has an 0.00 career ERA, which is the lowest any Hall of Famer has. However, he only threw 8⅓ innings over his career, which doesn’t meet the threshold I set. (He also gave up five unearned runs, seven hits, and six bases on balls, although he also struck out six batters.)

A few general notes on the above table:

More specific notes on several of the above players:

Devlin only started pitching in 1875. But then, his career length is deceptive: he pitched literally every inning the Louisville Grays played in 1877, and almost as much in 1876. Since he was doing the work of an entire five-pitcher starting rotation and a bullpen, I’m pretty sure those two years count as at least twelve. Across his five-year career, he accomplished at least two feats that, like Spalding’s win%, will never be duplicated:

But obviously, he wasn’t technically a two-way player in 1877. (His career didn’t end abruptly due to an injury; the real reason is much more tragically foolish – see “Nothing new under the sun” below.) He is also said to have invented the pitch we now call the sinker, which is a large reason he was so dominant. He hit .287/.296/.352 and had a career 1.90 ERA (150 ERA+), which somehow only got him a 72–76 record.

O’Rourke technically was about ⅔ innings short of meeting the pitching requirement of MLB’s criteria for two-way play; I mostly included him because I like him. (How can you not like a player with a moustache like his?) He is notable as the first person to get a base hit in the National League as a Boston Red Stocking (no, not the modern Boston Red Sox; the modern Atlanta Braves). He was a sober, eloquent player in a time when the Irish were subject to horrific discrimination and stereotyping. He himself was remarkably free of such prejudices, to the extent that he signed the African-American player to his minor-league Bridgeport Victors team, which continued to exist until 1932 under various names. (Herbert played four seasons for them, hitting .200/.200/.300 with one home run and five runs scored in thirty at-bats in his rookie 1895 season. I was unable to find stats for his later seasons.) I also find O’Rourke’s implacable opposition to the reserve clause endearing. Perhaps the most famous example of the eloquence that earned him the nickname ‘Orator’ comes in his response to shortstop Johnny Peters’ request of a $10 advance:

“The exigencies of the occasion and the condition of our exchequer will not permit anything of that sort at this period of our existence. Subsequent developments in the field of finance may remove the present gloom, and we may emerge into a condition where we may see our way clear to reply in the affirmative to your exceedingly modest request.”

Inspired by Ward (see below), he enrolled at Yale Law School and would pass the bar exam in 1887. Law served as an excellent outlet for his grandiloquence; he practiced until his death from pneumonia at age 68. He was one of the earliest nineteenth-century inductees to the Hall of Fame.

Ward, undoubtedly one of the greatest defensive players in the history of baseball, only pitched until an injury ended his pitching career in 1884, but was almost as much a workhorse as Devlin until then. He remained a workhorse afterward, too, going so far as to teach himself to throw left-handed so that he could keep playing center field the same year. He also gets bonus points for not sharing contemporary prejudices, going so far as to attempt to sign Black pitcher George Stovey and Black catcher Fleet Walker to the New York Giants; unfortunately, their AAA club, the Newark Little Giants, refused to release them. (We’ll discuss them both more later.) On 1880-06-17, just five days after threw the first perfect game in MLB history, Ward threw the second. ( threw – eighty-four years later. As a result, the shortest span between perfect games in NL history immediately preceded the longest span between them.) At age 20 years, 105 days, Ward is the youngest pitcher ever to throw a perfect game. Ironically, his opponent that day, , is also a Hall of Famer.

(MLB’s rules were extremely different in 1880: foul balls were not counted as strikes; foul balls caught after a single bounce were counted as outs; pitchers were not allowed to throw above the shoulder, necessitating underhanded or sidearm pitching; batters had the right to call balls high, low, or belt-high; and umpires got sole discretion whether a pitch was “good” [a strike] or “unfair” (a ball). The six-foot-deep pitcher’s box [not a mound] also started forty-five feet from the batter’s box; contrast with the modern pitcher’s mound, which is elevated by ten inches and starts sixty feet from it. Also, players didn’t wear gloves, and ball fields were not maintained to modern standards, frequently causing balls to hop unpredictably. Whether this all made the accomplishment easier or harder is up for debate, but I’m going with “far, far harder”.)

Ward was instrumental in the formation of the short-lived Players’ League, which actually supplanted the National League and the American Association as the most successful baseball league in 1890 in terms of both talent and attendance, but was unable to secure stable enough finances to maintain long-term viability. (The American Association was likewise drained and would fold after the 1891 season.) Ward was also undoubtedly one of the smartest people ever to play baseball; he would eventually earn a law degree from Columbia University.

It should probably go without saying that Ward is one of my favorite baseball players of all time.

Ferguson’s career with the Philadelphia Quakers (now the Phillies) was cut tragically short by his death from typhoid fever at age 25. He pitched a no-hitter in 1885 and won twenty games in all four of his seasons as a major league pitcher. Hall of Fame player-manager , who played for the Quakers’ crosstown rivals the Athletics during Ferguson’s career, listed him as one of the five greatest ballplayers of all time (alongside , , , and ), calling him “a man who could pitch like a streak and play the infield, too.” In 1925, Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger sports editor Leo Riordan called Ferguson the greatest ballplayer who ever lived, even eclipsing Cobb, since “Ferguson could play every position on the team. One year he started to pitch for us and wound up on second playing as well as Eddie Collins.… No better baserunner ever lived.” In 1924, sportswriter W. B. Hanna called him:

“the game’s best all around player. There have been men who could look after as many positions, but none who could play them all so well. Ferguson was a pitcher, good enough to be a regular on any ball club of the present; he was a good second baseman, not just a filler-in, but good; he could play the outfield well enough to make the absence of the regulation no handicap, and he was a first class batter. There hasn’t been an all around man since his day to equal him.”

The Washington Senators’ Griffith Stadium was named after Clark Griffith, who purchased the team in 1919. They were effectively the era’s Tampa Bay Rays, as he ran the team on a shoestring budget by necessity until the NFL team now called the Washington Commanders moved into the stadium, enabling him to finally turn a sizeable profit. He was one of the first owners to sign Latin American players; he also reportedly tried to sign Negro League legend in the 1930s, but was blocked by this book’s arc villain, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Griffith also played a major role in popularizing night baseball, and his connections with Franklin D. Roosevelt may have secured permission for baseball to continue during WWII.

I’ll have much more to say about Gibson below, but a brief introduction to the man: